The purpose of this dissertation is to cover most of the important aspects involved in publishing information on the World Wide Web. Due to the nature of this course, I have placed much emphasis on graphics, sound and video, and how they are incorporated into a web site. As part of this dissertation, I have produced the Beever Web site which is situated on this server. Included in this site are examples of what I have worked on during the final year of my Media Technology degree.

The Web site was created as part of my group project and forms the homepages of a band called Beever, of which I am a member. The site has been created in such a way that it does not use features exclusive to any particular Web browser.

1 Background to the Internet

- What is the Internet?

- The World Wide Web (WWW)

- The Hypertext Markup Language

- The Web browser

As we reach the end of the twentieth century, great emphasis has been placed on the way in which we communicate with one another. Due to the advancements of the telecommunication network, and information technology, we are able to send and receive an increasingly greater variety of information.

The phenomenal growth of the Internet during the early nineties is fast becoming a very important part of the communication network. Personal computers are now common place in many homes, which has led to an increase in traffic on what is now known as the ‘Information Superhighway’.

It is not only individuals who are using the Internet to obtain information. Companies are now looking towards this technology to extend their line of business and reach new markets.

What is the Internet?

The Internet is a vast collection of computer networks that has developed since the sixties. One of the earliest networks that formed the basis of the Internet was the US Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (DARPANET). It was the first to interconnect government, academic and private research organisations with one of the early European networks known as the Conseil Europeen pour la Recherche Nucleaire (CERN) in Geneva. Today, that network has been extended to cover many millions of computers located across the entire globe.

The World Wide Web (WWW)

Initially, the Internet was used for sending electronic messages (Email), and transferring files. It did not take long for like-minded individuals to set up news groups, so that information could be shared amongst those interested in the same subjects. To allow people to obtain files from another system without having to send an email message to request the information, the File Transfer Protocol (FTP) was developed by the Internet community.

These early standards were useful in speeding up the interchange of information across the Internet. There were, however, limitations when it came to document handling. You could not be certain what format the document you were accessing was in, or if you were capable of processing it.

To overcome the problem of incompatible document formats, a researcher at CERN, Tim Berners-Lee, developed a document browser that could request files over the Internet and present them in a standard way. For this to be accomplished, two new standards had to be introduced. These were the HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP), and the HyperText Markup Language (HTML). From the CERN browser, the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) in the States developed the Mosaic browser. This soon became the standard application used to access documents on the Internet.

As these document browsers became readily available, an increasing amount of people placed information on the Internet. A standard method of identifying files using Uniform Resource Locators (URLs) was developed so the files could be shared more easily. This vast array of files that are interconnected in this way has formed what is known as the World Wide Web (WWW).

The HyperText Markup Language (HTML)

The term markup is used to describe codes that are incorporated into electronic text documents to define the structure of the content. All electronic documents employ some form of markup to describe the way in which it is formatted. This is not always apparent though, as certain word-processors hide these codes and only present the document as it should be viewed, unless instructed to otherwise.

Each word-processing program has its own set of markup instructions, though some are capable of importing a document created in another program. Despite this, transferring a document between different word-processors and attempting to obtain the identical format is inconvenient and time consuming.

In an environment such as the Internet, the ability to read documents using a compatible markup system is extremely important. It is for this purpose that Berners-Lee developed HTML. HTML is implemented using the Standard Generalised Markup Language (SGML). SGML is an internationally recognised standard for text information processing, providing the means to distribute, search, and retrieve electronically stored text. Documents marked up in SGML have two elements. The first is the content, the information to be presented. The second is information on the basic structure of the document. This is an ideal way to distribute documents, as the information is platform independent. Anyone with a computer and the necessary software (a client) can read information marked up in this way. As SGML only identifies the nature of the content, it is the reader’s responsibility to determine how the different levels of meaning are displayed. The convention soon arose that if the client software could not understand any markup, it would display the content without the benefit of the structural code associated with it.

Since the very first implementation of HTML, it has gone through many revisions. In the past, problems arose as the language was developed. The standards that were supposed to make HTML universal were becoming eroded. To combat this, an organisation was created in the 1994 to attempt to bring some much-needed order to the world of HTML. Known as the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), its goal was to develop common standards for the evolution of the World Wide Web.

Presently the language has reached version 4.0, and has incorporated features to make use of many other programming technologies. With major companies such as Microsoft and Netscape incorporated as members of the W3C, it is hoped that the standards for the Internet will be adhered to by all. This includes the software used to view HTML documents – the Web Browser.

The Web browser

Before the modern Web browser, users accessed information on the Internet with computers that emulated standard text based terminals. This restricted the type of information that could be published on the Net. There were no sound, animations or virtual environments.

As CERN developed the World Wide Web, this situation changed. A graphic environment was required which would allow images to be added to text information. The most groundbreaking browser, Mosaic, developed by NCSA, made this possible. Mosaic became the most popular Web browser, because it was free, and available on a variety of platforms.

Despite the fact that HTML documents are platform independent, the user’s platform and browser can affect how a page is viewed. It also can determine what can be accessed from a particular Web site. Many different platforms and browsers are used by individuals to access the Web, and this has to be taken into consideration when planning a site.

The two most popular Web browsers used today are Microsoft’s Internet Explorer, and Netscape’s Navigator. Both are now free to obtain, and are presently at version four of their development.

Mosaic

Now that it has been superseded by other more powerful browsers, the final version of Mosaic has been released. NCSA no longer offers any technical support for the browser.

Mosaic offers most of the features required by Web developers, including tables, frames, and client-side image maps (all explained in later chapters). It does not support any HTML standards higher the HTML 3.2, as Mosaic 3.0, the final version, was completed in 1996.

Netscape Navigator

The first graphic browser that really showed what the Internet had to offer, was Netscape Navigator. The present version of this browser, Netscape Navigator 4.0, is part of an integrated suite of Internet tools called Communicator 4.0.

Internet Explorer

Software giant Microsoft almost missed the boat with respect to the Internet. It believed that the Internet would be too slow and unworkable to be of any use, underestimating the Web’s potential. Before Microsoft realised the enormous mistake it had made, Netscape had already gained a foothold on the browser market. Quickly, Microsoft developed it’s own browser to rival Netscape’s. This began what is known as, rather dramatically, the ‘browser wars’.

Contents

2 Basic HTML

- Structural elements

- Basic text formatting

- Organising information using lists

- Tables and page layout

- Hyperlinks

An HTML document is a small text file that is usually downloaded over the Internet, but can be used as a standard for all kinds of documents. To begin with, an HTML document has its own filename extension, html or htm. For example:

Document.html

Homepage.htm

If a dedicated HTML text editor is used to create the document, the extension will be added automatically. Otherwise, the author must save the document with this extension manually.

Structural elements

HTML documents use standard markup codes known as tags to describe to the browser how the document is formatted. These formatting tags can be seen when an HTML document is viewed using a standard text editor.

An HTML tag is a command string that is enclosed within a less than (<) and a greater than (>) sign. For example:

<TITLE>

<HR>

An opening tag is any tag in which the string does not begin with a slash (/). The end or closing tag is any tag in which the string does begin with a slash (/). The inclusive region between the opening and closing tag with the same string is known as an element. Note that not all elements require closing tags. How a browser interprets an element depends on the tags that surround it. For example, the <TITLE> tag informs the browser what the author has called that document, i.e.:

<TITLE>This is John Smith’s Homepage</TITLE>

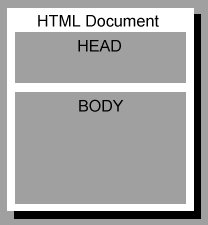

A well constructed HTML document will conform to a certain layout. Open any of the HTML documents included on the CD-ROM for an example. The architecture of such a document is shown in Figure 2.1 as follows:

Figure 2.1: Structure of an HTML document.

In HTML, this translates as the following code:

<HEAD>

. . . . . .

<HEAD>

<BODY>

. . . . . .

<BODY>

<HTML>

The whole of the document structure consists of nested elements. The outermost element is an <HTML> element, beginning with the <HTML> tag and ending with the </HTML> tag. The rest of the document is nested within this element.

The two primary sub-components nested within the <HTML> element are the <HEAD> and <BODY> elements. These elements both appear within an <HTML> element, but neither are nested within the other. The <HEAD> element contains metainformation about the information contained within the <BODY> element. This metainformation does not have any visible effect on how a browser views the document, but the browser does have access to this information. The following code is a very simple HTML document:

<HTML>

<HEAD>

<TITLE>A very simple HTML document</TITLE>

</HEAD>

<BODY>

This is an example of a very simplistic HTML document

</BODY>

</HTML>

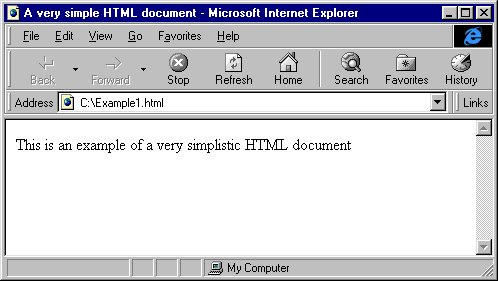

The result of how a browser renders this code is shown in figure 2.2. The <TITLE> element dictates the title appearing in the top of the user interface window. The contents of the <BODY> element appears in the display area.

Figure 2.2: Rendering of example document in Microsoft’s Internet Explorer.

Basic text formatting

Once the framework for an HTML document is considered, the content material can be placed into the document. Just placing text between the <BODY> tags within a document makes reading a very tedious task. Web browsers do not read text the way we do. At the end of a line, it adds a space and continues. This results in a completely unformatted document that appears unattractive. A basic text document needs formatting tags to tell the browser how to organise the text.

When you read a document of any description, you usually start with the title. In HTML the <Hn> tag is used to define a title heading, where n is an integer from 1 to 6. For the most important heading the value one would be used, down to six for the least important. A new paragraph is always started for a heading, and any material following it is placed on the next line.

As stated previously, a browser will not apply any formatting to a document unless it is told. To break text up the paragraph tag <P> is used at the beginning of a new paragraph. The closing </P> tag is optional and can be omitted. When the browser interprets a paragraph tag, it adds a line space between the previous paragraph. To break up text without including a line space, the <BR> tag is used.

Other useful HTML formatting tags can be used to determine how the text appears in a document. These tags are divided into two categories, known as logical and physical styles. When using logical styles, the browser decides how to display the text based on the capabilities of the machine upon which it is being viewed. This allows the document to become more platform independent, whilst maintaining some consistency. Figure 2.3 shows the logical styles, and how they are typically displayed within a browser.

| Element |

Style |

| <ADDRESS> |

Italics |

| <BLOCKQUOTE> |

Normal with indent |

| <CITE> |

Italics |

| <CODE> |

Monospace |

| <DFN> |

Italics |

| <EM> |

Italics |

| <KBD> |

Bold Monospace |

| <SAMP> |

Monospace |

| <STRONG> |

Bold |

| <VAR> |

Italics |

Figure 2.3: Logical element styles

Using physical styles allows a web designer to apply more rigid formatting to text, creating a more finely tuned appearance. Physical styles are shown in figure 2.4.

Element |

Style |

| <I> |

Italics |

| <B> |

Bold |

| <U> |

Underlined |

| <STRIKE> |

Strike-through |

| <SUP> |

Superscript text |

| <SUB> |

Subscript text |

Figure 2.4: Physical element styles

A closing tag must be added when using logical or physical styles, otherwise the browser will often format the rest of the text using the opening tag.

With HTML 3.2, it is possible to change the type, size and colour of text, overriding the browser's default selection. This is achieved using the <FONT> element, with the following syntax:

<FONT FACE="1st choice, 2nd choice" SIZE="n"

COLOR="name or RGB value"> ...text to apply style to... </FONT>

The FACE attribute decides what font is applied to the text. If the first font is not available on the user's system, the second specified font will be used. Using the SIZE attribute will vary the size of the text, where n is a number between 1 and 7. Entering a RGB hexadecimal triplet in the COLOR attribute will change the colour of the text. Sixteen standard colours can be applied instead of using a hexadecimal number. These are: Black, green, silver, lime, gray, olive, while, yellow, maroon, navy, red, blue, purple, teal, fuchsia, and aqua.

Once the text has been formatted, it is often useful to separate passages into logical sections. To achieve this, the <HR> element is used to place a horizontal rule on a page. Using this, and the other tags described, ensures that documents will have maximum impact.

Organising information using lists

HTML uses special tags solely for the purpose of displaying lists. If a list is to be used to indicate a specific sequence of events or priorities, then the ordered list <OL> element is used. The code below is an example of how it is applied:

<OL>

<LI>First item

<LI>Second item

<LI>Third item

</OL>

Note that each list item has it's own <LI> tag. This causes the browser to start the item on a new line with the next number in the list. For example:

- First item

- Second item

- Third item

The numbering system used for a list can be altered using the TYPE attribute within the <OL> element, as in the following syntax:

<OL TYPE=value>

Where value is determined from a selection of five characters. Figure 2.5 gives examples of the five numbering systems.

| Value |

Numbering system |

Example |

| 1 |

Arabic |

1,2,3,... |

| A |

Uppercase alpha |

A,B,C,... |

| a |

Lowercase alpha |

a,b,c,... |

| I |

Uppercase Roman |

I,II,III,... |

| i |

Lowercase Roman |

i,ii,iii,... |

Figure 2.5: Numbering systems using the TYPE attribute.

When a set of items are related to one another, but do not need to follow any particular order, the unordered list <UL> element is used. Items are placed in this list using the <LI> tag as before, but are represented using bullets instead of numbers. For example:

- First item

- Second item

- Third item

The actual style of bullet used depends the browser, but it can be altered using the TYPE attribute set to circle, square, or disc.

Another type of list tag is <DL>, used to create a definition list. The difference between this and previous lists, is that two items are required for each entry. These items are the term, and it's definition, and are defined using the <DT> and <DD> tags. The syntax is:

<DL>

<DT>Term 1<DD>Definition 1

<DT>Term 2<DD>Definition 2

</DL>

The way in which these tags are implemented varies from browser to browser, but commonly it will appear as follows:

- Term 1

- Definition 1

- Term 2

- Definition 2

Using any of the list tags presents a simple option for formatting text. To employ a greater control over the presentation of text, a more powerful tool is required.

Tables and page layout

Within HTML, tables have been established as one of the most frequently used methods for arranging Web pages. Originally introduced to facilitate the formatting of tabular data, the table tags can be used far more creatively. The problem with HTML tables is that though they are two-dimensional by design, they must be coded in a linear fashion within an HTML document. This can make it hard to keep track of where information is going to appear within the table.

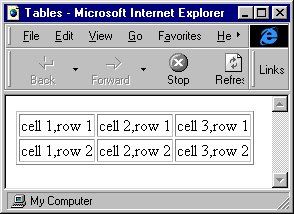

To create a table the <TABLE> tag is used, with the closing </TABLE> to mark it's end. Tables are divided into rows and cells. To begin and end a row, the <TR> and </TR> tags are used. With a row, each cell begins and ends with the <TD> and </TD> tags. The following is a the code for a simple HTML table:

<TABLE BORDER="1">

<TR>

<TD>cell 1,row 1</TD>

<TD>cell 2,row 1</TD>

<TD>cell 3,row 1</TD>

</TR>

<TR>

<TD>cell 1,row 2</TD>

<TD>cell 2,row 2</TD>

<TD>cell 3,row 2</TD>

</TR>

</TABLE>

This table consists of two rows of three cells. The BORDER attribute added to the <TABLE> tag creates a one pixel border for the table. How this table is typically displayed is shown in figure 2.6.

Figure 2.6: A simple HTML table.

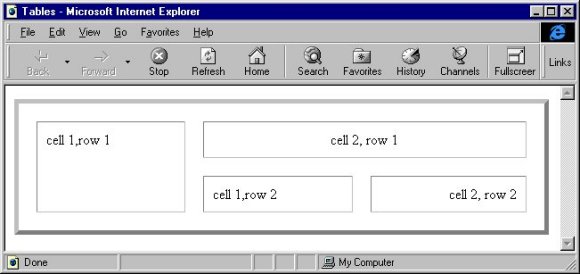

Various other attributes can be added to the <TABLE> tag to assert more control over the table. The width and placement of the table can altered using the WIDTH and ALIGN attributes. The space around items within a cell, and the space between cells, are varied used the CELLSPACING and CELLPADDING tags. The full syntax is as follows:

<TABLE WIDTH="n" ALIGN="left, right, or center" CELLSPACING="n"

CELLPADDING="n" BORDER="n"> ...table information... </TABLE>

Attributes can also be used to apply format instruction to rows and cells. The table row tag <TR> can use two attributes, ALIGN and VALIGN to position information horizontally and vertically. The syntax here is:

<TR ALIGN="left, right, or center" VALIGN="top, middle, bottom, or

baseline"> ...row information... </TR>

The same attributes applied to the <TR> tag can used to alter the format of the table cell <TD> tag. This tag also employs the use of the COLSPAN and ROWSPAN attributes to specify how many rows and columns a cell should stretch over. Like the <TABLE> tag, the WIDTH attribute can be used to set the width of an individual cell.

All of these attributes can be used to create a more interesting table. Every row can be formatted individually from the table, and every cell can be formatted individually from a row. Figure 2.7 shows what can be achieved with the following code:

<TABLE WIDTH="200" ALIGN=" center" CELLSPACING="20"

<CELLPADDING="10" BORDER="5">

<TR ALIGN="center" VALIGN="top">

<TD ALIGN="left" ROWSPAN="2">cell 1,row 1</TD>

<TD COLSPAN="2">cell 2, row 1</TD>

</TR>

<TR ALIGN="right" VALIGN="bottom">

<TD ALIGN="left">cell 1,row 2</TD>

<TD>cell 2, row 2</TD>

<TD ALIGN="center">cell 3, row 2</TD>

</TR>

</TABLE>

Figure 2.7: Table with formatting applied to each row and cell.

Tables come into their own when attempting to defeat the layout restrictions that are imposed by HTML. Using no borders for a table creates the impression of a seamless layout within a document.

Hyperlinks

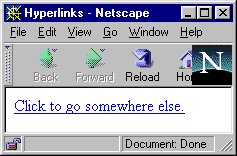

The most attractive feature of the World Wide Web is the ability to wander from different places using links to find anything of interest. This is achieved using hyperlinks, which are embedded within a document. Clicking on links on a hypertext page is far easier to navigate than using a full URL of a destination.

A hyperlink is placed on a page using an HTML tag called an anchor. The anchor tag <A> requires a closing counterpart, with the description text for the hyperlink placed between. The HREF attribute is required to inform the browser of the destination of the link, as follows:

<A HREF="URL">Link description</A>

The URL address can be anything including, other HTML documents, files, or supported multimedia. Different browsers display the link in various ways, but usually, unless directed otherwise, the link will appear is underlined blue text. It should be noted that other objects could be used as a hyperlink in place of simple text.

Figure 2.8: A typical hypertext link.

Hypertext is the key to the success of the Internet, forming the basis of Web navigation. Using hyperlinks transforms simple documents into major junctions, containing links to a multitude of destinations.

Contents

3 Programming

- Java

- JavaScript

- Visual Basic Script

- ActiveX components

Though HTML has been successful in providing a standard for marking up text, it does have certain limitations. When browsing standard Web pages on the Internet, it does not take much to realise that it is a one way experience. Using HTML alone, there is little that can be done to allow a viewer to interact with the information presented by the browser.

HTML documents are also rather static by nature, despite the fact that certain features have been added to the language, since it’s conception, to make them more dynamic. With the advent of more powerful computers, presenting visual and audio experiences has become very important. It is now necessary to have the option of incorporating an array of multimedia into a standard Web document.

To overcome the limitations of HTML, various programming methods have been introduced. These programming languages have been specifically developed for the Internet.

Java

Java has been touted as the most important development to have happened to programming for many years. It is neither a fundamental nor a theoretical change as developments go. In fact, there is little about the Java language that is particularly radical. Java is best described as a collection of existing ideas that have been streamlined and tidied up. More importantly, the industry surrounding the Internet has decided that Java is the language of the World Wide Web.

Java was originally intended for use in handheld machines and consumer electronics. For this purpose, it had to be compact and able to run on anything. It is these qualities that made it perfect for an Internet language, i.e., quick to download onto a multitude of machines.

The Java language was developed in 1991 by Sun Microsystems, a company known for its UNIX workstations. It took a while before its virtues as a Web language were recognised, but in 1994 Sun produced a Web browser called HotJava, that was capable of downloading and executing Java programs. Not long later, Netscape included Java in its Navigator browser, and from that point onward, Java’s future was secured. Presently, Microsoft’s Explorer also supports Java.

Java is both a compiled and interpreted language. Like HTML, a Java program can be written using a standard text editor. It is saved as a source file using the java filename extension, for example:

java source code.java

This program is then compiled into a byte-code format known as a class file, i.e.:

java source code.class

Sun Microsystems provide a compiler that performs this task. The code that is created cannot be directly understood by a computer processor, and so a software interpreter is used to execute compiled Java programs. This virtual microprocessor is called the Java Virtual Machine. The way in which this process is carried out is not unlike that of emulation software that allows you to run programs developed for one type of computer, such as an Intel PC, on another, such the Macintosh. The Java byte-code is very similar to the native machine code instructions that computers understand. This gives Java the performance that comes close to that of native compiled languages.

It is because the Java code is executed by an interpreter, that Java programs will run unmodified on any platform that the Java interpreter has been developed for. The interpreter is capable of checking the code for any questionable activity before executing it. This means that it is able to prevent a program from accessing areas of a system it has no right to, making Java a very secure language.

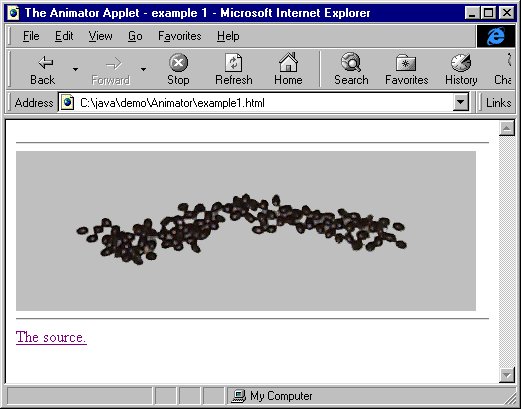

Java can be used to create standalone applications. Sun Microsystems HotJava browser is an example of a program written entirely in pure Java. The easiest method of creating a Java program is to embed an applet within an HTML document. Applets are small programs that are executed within a Java compatible browser. To call an applet in HTML, the <APPLET> tag is used to refer to the applet's compiled .class files. These should be included in the same directory as the document the applet is to appear in. Within this tag, the applets parameters are controlled using many <PARAM> tags. An example of this, is the frequently used Animator applet, created by Sun Microsystems. This applet allows a Web author to add animations with synchronised sound to a document. The following example code shows how this is achieved:

<html>

<head>

<title>The Animator Applet - example 1</title>

</head>

<body>

<hr>

<applet code=Animator.class width=460 height=160>

<param name=imagesource value="images ">

<param name=backgroundcolor value="0xc0c0c0">

<param name=endimage value=10>

<param name=soundsource value="audio">

<param name=soundtrack value=spacemusic.au>

<param name=sounds value="1.au|2.au|3.au|4.au|5.au|6.au|7.au|8.au|9.au|0.au">

<param name=pause value=200>

</applet><hr>

<a href="Animator.java">The source.</a>

</body>

</html>

In this example, ten images are used to create the animation, which are placed in a directory called images. These images are either GIF or JPEG files and, in this example, are synchronised with ten audio samples. The samples must be in Sun's .au format. Unless told to otherwise, this animation will repeat indefinitely. While the Java Animator applet is a far from ideal solution for incorporating animations into documents, it can be useful if the graphic and audio file sizes are kept to a minimum.

Figure 3.1: Example animation applet running under Internet Explorer.

JavaScript

JavaScript was originally introduced to the Netscape browser, but is now featured in Internet Explorer as well. It is a powerful, fairly easy to use method of scripting events, objects and actions. JavaScript can be used to accomplish tasks that previously would have required Java to perform. Like Java, JavaScript is an object-orientated based scripting language Though less extendable, it is simpler to use.

JavaScripts are executed directly in HTML pages and do not need to be compiled. To include a JavaScript in a HTML document, the <SCRIPT> tag must be used in the following format:

<SCRIPT LANGUAGE="JavaScript">

. . . . . .

</SCRIPT>

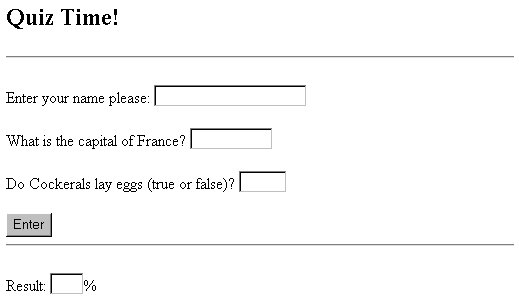

The JavaScript code is placed between the <SCRIPT> tags. The following JavaScript is a simple quiz game, used as an example of what can be done with the language in an HTML document:

<HTML>

<HEAD>

<TITLE>A JavaScript Demonstration</TITLE>

<SCRIPT LANGUAGE="JavaScript">

function doform(form) {

if (confirm("Are you certain "+document.forms[0].name.value+"?")){

score=0

if (document.forms[0].question1.value=="Paris"){

score=score+1; }

if (document.forms[0].question2.value=="false"){

score=score+1; }

form.score.value = (score / 2)*100

}

else alert ("Please come back again.")

}

</SCRIPT>

</HEAD>

<BODY>

<H2>Quiz Time!</H2>

<HR>

<FORM>

Enter your name please;

<INPUT TYPE="text" NAME="name" SIZE=20><P>

What is the capital of France?

<INPUT TYPE="text" NAME="question1" SIZE=10><P>

Do Cockerals lay eggs (true or false)?

<INPUT TYPE="text" NAME="question2" SIZE=5><P>

<INPUT TYPE="button" VALUE="Enter" ONCLICK="doform(this.form)">

<HR>

<BR>

Result;

<INPUT TYPE="test" NAME="score" SIZE=5

<BR>

</FORM>

</BODY>

</HTML>

Within the <BODY> element of the document is a standard HTML form. This contains the questions for the participant to answer, and for the JavaScript in the <HEAD> element to process. Figure 3.2 shows how it looks when viewed on a browser.

Figure 3.2: Form to be processed by a JavaScript

The code for this form is fairly typical HTML, except for the ONCLICK event handler, which is a Java Script extension. This causes the JavaScript doform() function to run when the user clicks on the ‘Enter’ button. When this button is pressed, four fields of information are sent to the function:

- The first is the participants name, defined by the first <INPUT TYPE> tag and referenced by the code document.forms[0].name

- The second is the answer to question one, and is defined by the second <INPUT TYPE> tag and is referenced by the code document.forms[0].question1

- The third is the answer to question two. This is defined by the third <INPUT TYPE> tag and is referenced by the code document.forms[0].question2

- The last field of information is the score, which is defined by the fifth <INPUT TYPE> tag. This is referenced by the code document.forms[0].score

The value of any of these fields can be obtained by adding .value to the reference for that field, i.e.:

document.forms[0].name.value

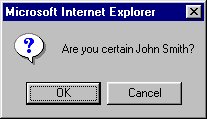

The JavaScript allows the participant to back out of entering the answers they have placed in the form. The following code is used:

if (confirm("Are you sure "+document.forms[0].name.value+"?")){

This displays a dialogue box, as shown in figure 3.3, in the user’s window. The result from the dialog box is then processed by the if statement. If the user clicks on the ‘Cancel’ button, the function executes the else statement, and puts up an alert box containing the message "Try again." The function then exits, returning control back to the form.

Figure 3.3: A dialogue box created by JavaScript

If the user clicks ‘OK’, the function executes the code after the if statement. First it sets up a variable score, to equal zero. This will be used to calculate the user’s score. The information entered into the form are then compared with the correct answers, using the statements:

if (document.forms[0].question.1.value=="Paris"){

score=score+1; }

if (document.forms[0].question.2.value=="false"){

score=score+1; }

If a reply is correct, the variable score is increased by one. Finally, the percentage value of the score is calculated, and placed into the score field created by the form. When the function is completed, the updated score value appears in the field.

This is a very basic example of what JavaScript can do. Though it is a very rudimentary script, as it contains no error checking and is case sensitive, it shows that JavaScript can make certain tasks such as validating forms input very easy to achieve.

Visual Basic script

Though Netscape was the first to include JavaScript features in its browser, Microsoft was soon to incorporate the language in Internet Explorer. This was not enough for Microsoft though, so they developed a version of JavaScript called JScript. As usual they have added their own extensions to the language which are not supported by Netscape. In addition to this, Internet Explorer also implements a second scripting language called Visual Basic Script, also known as VBScript. VBScript is similar to JavaScript in terms of the functions it offers, though it bares closer resemblance to Visual Basic, from which it is derived.

VBScript is placed within an HTML document in a similar fashion to JavaScript, using the <SCRIPT> tag, but setting the LANGUAGE attribute to vbscript. Using VBScript allows you to create an interactive application within a Web page. It is useful for communicating with a user without having to send data back and forth to a server. A VBScript solution to this particular task could be to display a customised message box, when needed, to respond to an event. The following is an example of how this is achieved:

<SCRIPT LANGUAGE="vbscript">

Sub cmdButton1_OnClick

Alert "You've clicked this button"

End Sub

</SCRIPT>

Many <SCRIPT> tags can be placed within an HTML document, or all the subroutines can be placed within one set of tags. Also, it does not matter if the script is placed with in the <HEAD>, or the <BODY> element of a page. What does matter, is when the script is to execute, which depends on what it is supposed to achieve. Scripts can execute as a page downloads into a browser. A script can also execute due to an action carried out by the user. The final option, is a script that executes because it has been called by another script.

An area where VBScript is often used is the automation of standard HTML forms. A form is used within an HTML document as a front end for the user to input information. The principle element of a form is the <INPUT> tag. It defines the type of user interface to be placed within a form, such as, text boxes, option buttons, and checkboxes. A VBScript can be used to interface with these HTML controls by adding a script to the form.

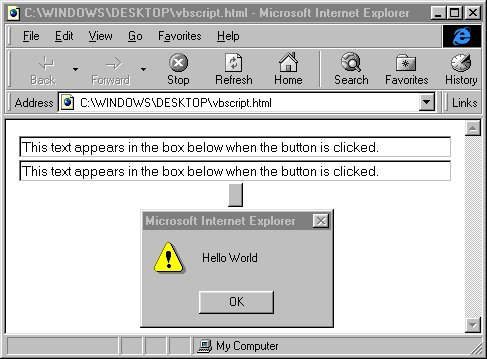

To achieve this, the control must be given a name by using the NAME attribute of the <INPUT> tag. This name is used by the script to identify the control, so it can act upon it. The following code is a simple example:

<HTML>

<HEAD>

<SCRIPT LANGUAGE="vbscript">

Sub button1_OnClick

form1.textbox2.Value = form1.textbox1.Value

Alert "VBScript executed"

End Sub

</SCRIPT>

</HEAD>

<BODY>

<CENTER>

<FORM NAME="form1">

<INPUT TYPE="text" NAME="textbox1" size="60"><BR>

<INPUT TYPE="text" NAME="textbox2" size="60"><BR>

<INPUT TYPE="button" NAME="button1">

</FORM>

</CENTER>

</BODY>

</HTML>

The HTML generates a form called form1, which consists of two text boxes, textbox1 and textbox2, and a command button called button1. When this button is clicked, the script assigns the Value property of the first text box to that of the second. The result is that whatever the user has typed into textbox1 is placed into textbox2 when button1 is a clicked. The script also presents an alert box displaying the message 'Hello World'.

Figure 3.4: Simple use of VBScript to interact with an HTML form.

VBScript is capable of much more complex tasks than just handling events within a standard HTML document. Microsoft has developed a technology that can be incorporated into a Web page, and controlled by VBScript. This technology is far more versatile than standard HTML, and is known as ActiveX.

ActiveX components

While most major companies were gearing up for expansion into Internet related business, software giant Microsoft was caught off guard. It did not take the company to long to realise that by adapting their present technology for the Internet, it would make huge inroads into the market.

Microsoft discovering the Internet was not so much a revolution, more a logical development of their tried and tested technologies. For several years, many Windows applications had been constructed using reusable software building blocks that are put together using a language such as Visual Basic. These building blocks are known as component object model (COM) objects. Microsoft gave COM a facelift, added Internet capabilities and called it ActiveX. What makes ActiveX attractive to an HTML developer is the fact the ActiveX components can be included in HTML documents for use on the Web.

While some ActiveX controls are self-contained, most need some sort of user interaction. To achieve this, VBScript is used to communicate between the browser and the ActiveX component. Using ActiveX and VBScript, it is possible to produce Web pages that can reproduce the functionality of Windows based applications.

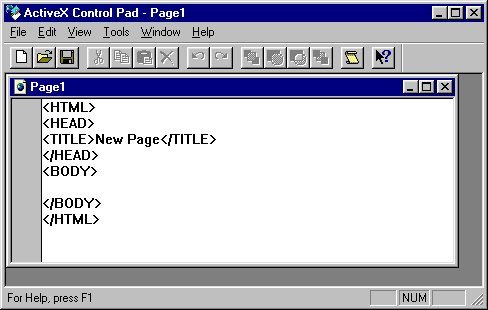

There are a range of ActiveX controls that are included with the full install of Internet Explorer. These controls are used to build forms similar to those of standard HTML, but are far much more versatile. If there is a need to create new ActiveX controls, a tool such as the Control Creation Edition (CCE) of Visual Basic 5 can be used. Third party ActiveX controls are available for an off-the-shelf solution. Whichever controls are used, the next task is to add them to an HTML document. All ActiveX controls have 128 bit identification numbers that are unique to a particular component. This identification number must be referred to within a Web page. Remembering these codes is somewhat tedious, so Microsoft developed the ActiveX control pad which is free to download from their Web site. When the control pad is run, it automatically starts with an HTML template ready to receive an ActiveX component.

Figure 3.5: The ActiveX Control Pad.

Using this application, it is possible to add a range of different controls to the HTML document, and then attach some scripting to the page. Control Pad has an automated scripting feature, though somewhat limited, is useful for adding VBScript to the controls. When the code is finished, the Control Pad adds the code into the document using the relevant <SCRIPT> tags, ready for the page to be viewed with a browser. It should be noted that only Internet Explorer is capable of understanding ActiveX controls.

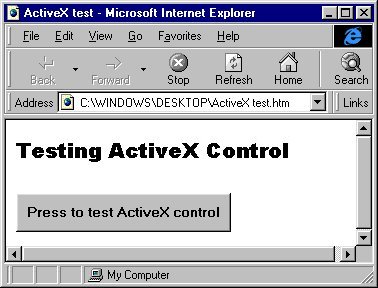

A very simple example that demonstrates how Control Pad is used would be to make a label change it's caption when a command button is clicked. First, the two objects must be placed within the body of the HTML document. This is achieved using the insert feature from the Control Pad's file menu to create the label and the command button. The properties of the two controls are changed to produce the desired front end. An example of what the code may look like is as follows:

<OBJECT ID="Label1" WIDTH=335 HEIGHT=39 CLASSID="CLSID:978C9E23-D4B0-11CE-BF2D-00AA003F40D0">

<PARAM NAME="ForeColor" VALUE="2147483656">

<PARAM NAME="BackColor" VALUE="16777215">

<PARAM NAME="Caption" VALUE="Testing Active X Control">

<PARAM NAME="PicturePosition" VALUE="524290">

<PARAM NAME="Size" VALUE="8858;1000">

<PARAM NAME="FontName" VALUE="Arial Black">

<PARAM NAME="FontHeight" VALUE="320">

<PARAM NAME="FontCharSet" VALUE="0">

<PARAM NAME="FontPitchAndFamily" VALUE="2">

<PARAM NAME="FontWeight" VALUE="0">

</OBJECT>

<OBJECT ID="CommandButton1" WIDTH=215 HEIGHT=39 CLASSID="CLSID:D7053240-CE69-11CD-A777-00DD01143C57">

<PARAM NAME="Caption" VALUE="Press to test ActiveX control">

<PARAM NAME="Size" VALUE="5680;1023">

<PARAM NAME="FontEffects" VALUE="1073741825">

<PARAM NAME="FontHeight" VALUE="200">

<PARAM NAME="FontCharSet" VALUE="0">

<PARAM NAME="FontPitchAndFamily" VALUE="2">

<PARAM NAME="ParagraphAlign" VALUE="3">

<PARAM NAME="FontWeight" VALUE="700">

</OBJECT>

This places a label an the page with the caption 'Testing ActiveX Control', and a command button that says 'Press to test ActiveX control'. To add some interaction to these controls, the Script Wizard feature is used. What happens when the command button is clicked can be assigned by selecting the click event of commandbutton1. Code can then be entered to change the caption of label1. When you have returned to the document, the script is automatically added to the page:

Sub CommandButton1_Click()

Label1.Caption="ActiveX is working correctly"

end sub

Now when this page is viewed in a browser, the label will display 'ActiveX is working correctly' when the command button is clicked.

Figure 3.6: ActiveX label caption changes when the command button is clicked.

This is obviously a very basic example of what ActiveX can achieve, but it is capable of producing highly complex Windows applications for the Web. ActiveX is, arguably, the most developed route to producing outstanding dynamic content. It's only drawback is the fact that only Internet Explorer is compatible with ActiveX controls. Despite this, ActiveX is a mature technology that has the commercial muscle of Microsoft behind it. This can only confirm the importance of ActiveX for the Internet.

Contents

4 Multimedia and the Web

- Graphic File Formats

- Audio

- Video

Originally, the Web was seen as a means of offering access to thousands of documents, but developments have seen it become far greater than just an electronic library. Now, Web sites are full of images, sounds, animation, and video media, increasing the possibilities that exist for mere text documents. This is what is known as multimedia.

Despite these advances, Web-based multimedia pales in comparison with standalone examples on CD-ROM. This is due to the inherent limitations of network communications and modem speeds, which do not exist between a computer and a connected CD-ROM device. Many developers are working to bring the quality of Web-based multimedia up to the standard of CD-ROM.

One criticism levelled at the computer industry, is the innumerable amount of standards and formats that are used within it. The Internet has its fair share, and these must be taken into consideration when incorporating multimedia files into a Web site. Multimedia on the Web is divided into two basic categories - internal and external. Internal multimedia content can be displayed inline as an integrated part of a browser. Any material that has to be handled outside the browser by another application falls into the latter category. If a Web author uses this type of file, and it is not widely used on the Internet, they will alienate those who wish to view the site. A well-managed Web site uses resources available to the majority of its target audience.

Graphic file formats

Due to the limited bandwidth available while accessing the Internet, it is not possible to use full, uncompressed bitmap images without a detrimental effect on download time. From the many different graphic file formats available, only two are used, almost exclusively, as far as the Web is concerned. These are GIF, and JPEG.

GIF

The Graphics Interchange Format (GIF) was invented by CompuServe, using a compression technique developed by Unisys. This format is commonly used to display images, using a maximum of 256 colours, in Web documents. GIF is a compressed format that is designed to minimise file transfer time over telephone lines. When saving an image as a GIF, you can specify how the image appears as it is downloaded. An interlaced GIF is gradually displayed in increasing detail as it is accessed by a browser.

One useful feature of the GIF89a format is the ability to specify a transparent colour in the image. When the image is loaded by a browser, the colour instructed to be transparent will not appear. This is useful for matching GIF files with the background colour of the page it is to be displayed.

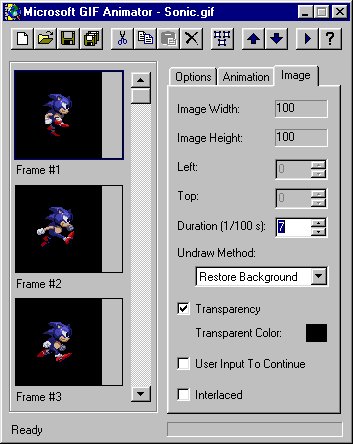

HTML also supports the use of animated GIF files in pages. An animated GIF file contains several images of a sequence that are displayed in turn to create a simple animation. This is probably the easiest method of incorporating animation into a Web page. The disadvantage with this method is that the files are usually very large, which can take a long time to download. A browser that does not support the animation part of a GIF will only display the first image in the sequence.

Figure 4.1: Microsoft’s freeware GIF Animator software

JPEG

The Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG) format is commonly used to display photographs and other continuous-tone images on the Internet. Unlike the GIF format, JPEG retains all the colour information in a full colour image. JPEG also uses a compression scheme that effectively reduces file size by identifying and discarding extra data not essential to the display of the image. When a JPEG image is viewed by a browser, it is automatically decompressed.

Because it discards data, the JPEG compression scheme is referred to as lossy. This means that once an image has been compressed and then decompressed, it will not be identical to the original image. A higher level of compression results in lower image quality, while a lower level of compression results in better image quality. In most cases, compressing an image as a high quality JPEG produces a result that is indistinguishable from the original.

Similar to interlaced GIF files, JPEG files can be progressive. This option displays the image gradually as it is downloaded from a Web browser, using a series of scans to show increasingly detailed versions of the entire image until all of the data has finished downloading. However, progressive JPEG images require more RAM for viewing and are not supported by all Web browsers.

For online display, such as the World Wide Web, JPEG images give the best colour reproduction, and the smallest file size. JPEG images are more suitable for photographs or high quality images. If an image contains line art or needs to have transparent areas, then the GIF89a format is more appropriate.

PNG

The Portable Network Graphic (PNG) format, developed as a replacement for GIF, includes features that are similar to the JPEG format. Like JPEG, PNG preserves all colour information in an image, using a low information loss compression scheme to reduce file size. A PNG image can also be interlaced, to display the image in gradually increasing detail as it is downloaded. PNG could be the graphic file format standard of the future for the Internet.

Audio

Audio can be used in a variety ways over the Internet. Sound effects or music can be played as soon as a page is accessed, using supported audio formats within standard HTML. More exotic types of audio data require the use of an external application or plug-in, to be installed into the browser.

Wave files

The majority of today’s personal computers come equipped with the necessary means to record and manipulate audio. The simplest way of including sound in an HTML document is to use the Windows PCM waveform (.WAV) format. The standard Windows PCM waveform contains PCM coded data, which is pure uncompressed pulse code modulation formatted data, similar to that encoded on a Compact Disc. A simple hypertext link can be used to connect a page to a sound file:

<A HREF="audio.wav">Link to sound file</A>

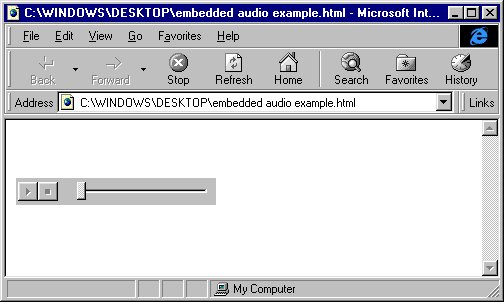

When the user clicks on the link, the sound file audio.wav starts downloading. When it is complete, the file can be played using an external player that will pop up outside the browser. The file can be embedded within a Web page using the <EMBED> tag, as follows:

<EMBED SRC="audio.wav" AUTOSTART=TRUE LOOP=FALSE WIDTH=200 HEIGHT=70></EMBED>

This tag works just like the <IMG> tag, telling a browser where to find a specified audio file. Using the AUTOSTART=TRUE attribute makes the browser play the file as soon as the document is loaded. Changing the attribute to AUTOSTART=FALSE means the user has to click the play button to hear the sample. The WIDTH and HEIGHT attributes control the size of the audio player’s control bar.

Figure 4.2: Audio control bar embedded within a Web page.

It is also easy to incorporate background audio into a Web page by using the following code:

<BGSOUND SRC="audio.wav" LOOP=4>

This instructs the browser to play the audio file 4 times. It is interesting to note that the <BGSOUND> tag is not pure HTML. In is an extension used by Microsoft’s Internet Explorer browser, and will not work with any other.

MPEG Layer III

Without data reduction, digital audio signals typically consist of 16 bit samples recorded at a sampling rate more than twice the actual audio bandwidth to maintain quality. In storage terms, this would require more than 1400 kbits to represent just one second of stereo music at the same quality of a compact disc. Without audio coding, downloading uncompressed high quality audio files from the Internet would result in huge download times. For an average Internet connection, a three minute stereo track from a compact disc would require a download time of more than two hours. To overcome this, audio on the Internet calls for an audio coding scheme that maintains sound quality as much as possible and allows real-time decoding on a large number of computer platforms without the need for any dedicated add-on hardware.

Figure 4.3: Nullsoft's Winamp. Decodes MPEG Layer III audio in real-time.

By using MPEG audio coding, it is possible to reduce the original audio data by a factor of 12, without losing sound quality. Factors of 24 and even more still maintain a sound quality that is significantly better than what you get by just reducing the sampling rate and the resolution of the audio sample. This is achieved by using what is known as perceptual coding, a technique that removes parts of the audio information that is not perceived by the human ear. Layer III is the most powerful member of the MPEG audio coding family as it achieves the highest sound quality for any given bit rate. Software decoders that make use of this technology, like Nullsoft's Winamp, are freely available on the Internet.

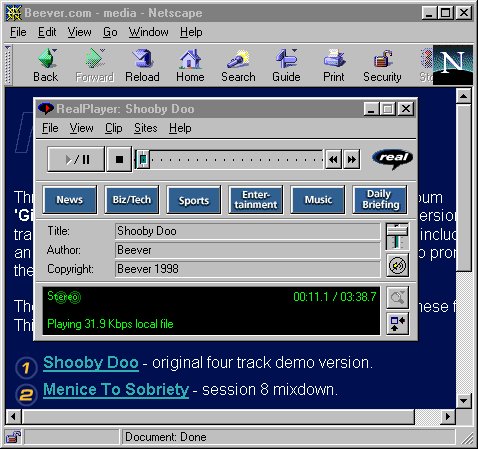

RealAudio

RealAudio is an audio format optimised for streamed playback over (usually) slow networks such as the Internet. Developed by Progressive Network's, a plug-in device is used to play back a continually downloading steam of data, negating the need to wait for the file to download. This feature has been instrumental in its use in live broadcasting over the Internet.

Figure 4.4: Navigator using Progressive Network’s RealPlayer 5.0.

RealAudio files can be added to a Web page just like any other audio file, but use the RealAudio .ra file extension. The audio data needs to be encoded before it can be streamed, using either the Progressive Network’s RealAudio Encoder, or an audio-editing package that supports the format.

Using RealAudio is a trade between file size and sound quality, and depends on the speed of the network used to broadcast the file. Very large uncompressed audio information of a number of megabytes can be compressed to kilobytes using this method, but the resulting audio is nowhere near the quality of a Compact Disc. Because of the low fidelity nature of RealAudio, it is often used by top radio and news networks such as C-SPAN, and ABC.

Video

One of the most exciting areas of the Internet is video broadcasting. It is also the most difficult to achieve because even heavily compressed video files can be extremely large. Not many visitors to a Web site will have the patience to wait for a huge video to download, unless it is extremely interesting.

Standard video formats

There are several methods of including video material into a Web site. The two most popular standards for the World Wide Web are Microsoft’s Video for Windows (AVI) and Apple’s QuickTime (QTW) format. Unlike audio data, which can be played back from a computer’s hard drive completely uncompressed, it is impossible to play video files without using compression. This process removes or reconstructs data to decrease the size of a file. As you compile a Video for Windows or QuickTime file, you compress the data to reduce the file size and facilitate the playback of the video. If one of these formats is to be used to send video information over the Internet, then the compression ratio has to be very high, which will result in a low quality video.

Figure 4.5:

A Video for Windows (AVI) file. |

Figure 4.6:

Apple’s Quick-Time (QTW) format. |

Like audio wave files, providing a hyperlink to a video file is the easiest method of adding it to a Web document. When the link is clicked, the file is downloaded and an external player starts up outside the browser.

MPEG compression

In 1988, the International Standards Organisation (ISO) of the International Telecommunication Union established the Moving Pictures Experts Group (MPEG) to agree on an internationally recognised world-wide standard for the compressed representation of video, film, graphic and text materials. The committee's goals were to develop a relatively simple, inexpensive, and flexible standard that placed most of the complex functions at the transmitter rather than the receiver. In 1991, the MPEG 1 standard was introduced to handle the compressed digital representation of non-video sources of multimedia. However, some manufacturers soon discovered that MPEG 1 could be adapted for the transmission of video signals. Since then, the higher quality and more versatile MPEG 2 standard has been developed.

MPEG video has gained popularity because it can maintain a reasonable image whilst using high compression ratios. This makes it an ideal video format for the World Wide Web.

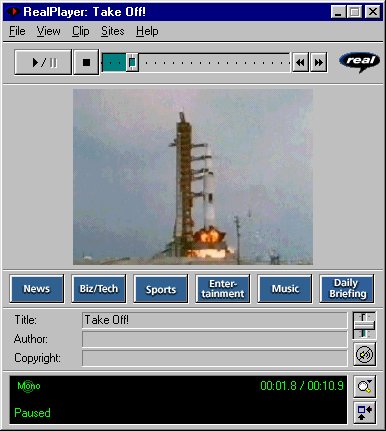

RealVideo

RealVideo works the same way is its audio counterpart, RealAudio, and is viewed using the same RealPlayer browser plug-in.

The concept of streaming video has the greatest potential of all the video formats for the Web. After a small portion of the data is downloaded, the video can be viewed while the rest of the file is accessed. This sounds good on paper, but the technology is not quite refined yet. For a video to be convincing, it needs to achieve a playback rate of thirty frames-per-second. This is not quite possible over a standard telephone line, in fact it is more likely that the video could end up appearing like a low quality slide show.

Figure 4.7: Streaming video playback using Progressive Networks RealPlayer software.

Contents

5 Authoring Tools

There are two ways to produce HTML documents. The first is to create the document using a standard text editor, and add all the tags manually. Then you would check the document using a browser. This method certainly works, but is a very time consuming way of producing an HTML document.

Today, there is plenty of software specifically designed to do this task using more automation. The newest tools offer what is known as WYSIWYG – What You See Is What You Get, though even these have not really kept up with present advancements of the World Wide Web.

HTML Editors

HTML editors come in two varieties, which are HTML source, and WYSIWYG editors. The former are usually little more than a text editor that has been customised for the job of producing HTML. These editors allow you to edit the content of the document, but you are still working with tags in a traditional sense. Though many source editors provide intuitive support for many tags, a good knowledge of HTML is still needed to produce a document.

A more graphical approach is used by WYSIWYG editors. For example, if you wish to add a horizontal rule to a page, it will appear on the screen in the document. What you will not see is the <HR> tag that has been added to the document ‘behind the scenes’.

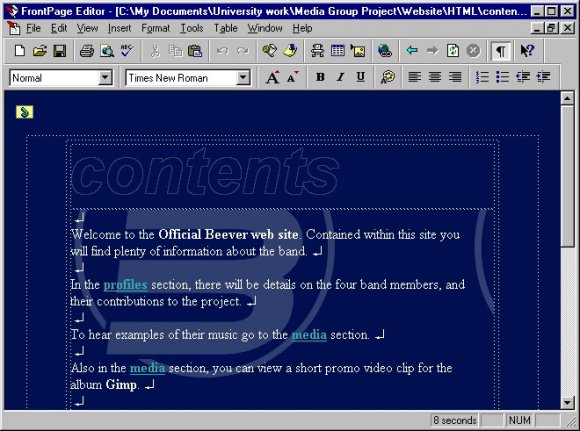

Microsoft FrontPage

As is the norm from Microsoft, FrontPage is not just one program, but an integrated suite of software used to author and manage Web sites. The authoring part of the suite, FrontPage editor, was one of the first to offer a WYSIWYG interface for creating Web pages. No knowledge of HTML is required, even when creating complex pages that can include objects such as Java applets and ActiveX controls.

One of the features that makes FrontPage useful for novice users, is its use of templates to speed up development of pages. Standard templates include, bibliography, table of contents, guest book, and what’s new. In fact, most of the types of pages included in a contemporary Web site. As well as the more specialised type of page, a normal page template is included which includes only the basic HTML structure tags.

Fig 5.1: Microsoft FrontPage. A high-end HTML editor.

Adobe PageMill

Originally only available for the Macintosh platform, one of the most popular HTML editors, Adobe PageMill, is now available for Windows 95. PageMill is a WYSIWYG editor, but has the option to switch to a source-edit mode. PageMill also provides the option to import documents from popular word-processing packages such as Microsoft Word and WordPerfect.

One useful option of PageMill is its ability to display hidden HTML code. The end user is able to view items such as comments, scripts, and anchors, while you edit. It also allows the creation of image maps, which can be a tedious task if done manually. Hyperlinks can be added by inserting tags manually, or they can be dragged from a browser. The links remain live from within the editor, eliminating the need to switch to a browser to test them.

Other features of PageMill include the ability to spell check documents, and support for tables and frames. Tables and frames are created by using a drag-and-drop interface to include them instantly into a page.

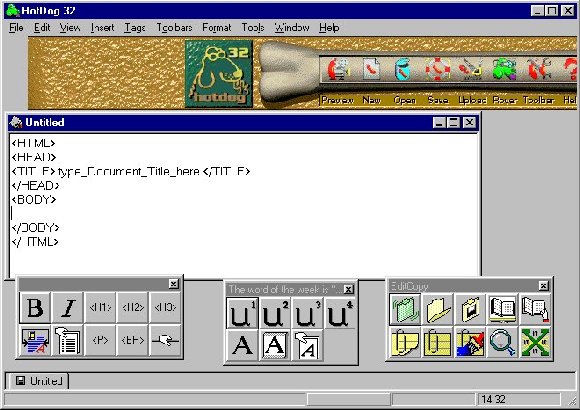

HotDog

In it’s early form, HotDog was not particularly functional, but did include an interesting dog character! The latest version of this HTML source editor is far more up-to-date, including Java, plug-ins, and style sheets. One of the more useful features of HotDog is the ability to customise its user interface. Users with special needs, who create their HTML pages in a certain way, would find this useful.

The program comes in two editions, standard and professional. With the standard version, you have to switch to an external browser to view the page. The professional version includes a browser interface called Rover, which behaves very much like Internet Explorer.

A feature recently added to HotDog, is support for style sheets. With style sheets, it is possible to implement font or page characteristics for an entire page without manually editing the whole document. When the pages are finished, HotDog includes FTP capability to transfer files to a server. Hog Dog is only available for Windows 95 and NT.

Fig 5.2: Hot Dog HTML editor. The canine sound effects do become annoying!

Netscape Composer

One of the newest HTML editors comes from Netscape, and is included as a part of it’s Communicator 4.0 suite. Composer is available for the Windows, Macintosh, and UNIX platforms, and is aimed at creating individual pages rather than site management.

As would be expected, Composer’s editing screen is very similar to the Navigator browser window, but also includes extra toolbars for HTML options. Using these functions gives access to links, tables, and paragraph formatting, but does not include support for frames or forms.

Netscape have integrated Composer tightly with Navigator, which enables HTML authors to drag-and-drop links from pages on the Web, straight into their own documents. Similarly, graphic files can be obtained and used in this way.

No templates are included with Composer, though you can download sample pages to edit from Netscape’s own Web site. Netscape also provide a CGI-driven script wizard to allow you to create a page with the desired appearance.

Composer is not, however, an effective solution for creating and managing Web sites. Nor is it very useful at creating complex HTML documents, which will limit its appeal.

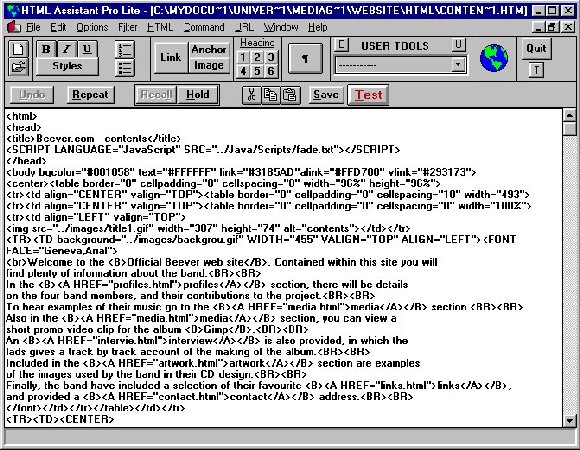

HTML Assistant

Available in two forms, Pro and Pro Lite, HTML Assistant is a useful source editor. The program includes special functions, including the ability to quickly and automatically extract and copy URLs from HTML files, like Netscape's Bookmark files, or NCSA's "What's New" page, for easy organisation and compilation into documents. It can convert HTML Assistant URL files, Cello Bookmarks and Mosaic .INI files to HTML text, as well as the automatic conversion of UNIX text files to DOS text. HTML Assistant has the ability to keep up with any changes in HTML, as the user can incorporate new tags into the software when necessary.

HTML Assistant Pro is an advanced version of HTML Assistant, which includes an automatic page creator function, a wizard-like feature which permits the rapid production of HTML documents. It can also filter out HTML tags from the text, and use additional filters to reformat text paragraphs.

Fig 5.3: HTML Assistant Pro Lite.

HTML Tools

Due to the industry that surrounds Web site creation and management, a whole plethora of utilities has been developed. These programs do not actually create original HTML code, but perform useful tasks that aid construction.

Bandwidth Buster

Available for Windows 3.1 and 95, Bandwidth Buster alters HTML files in an attempt to reduce the download time for those who are to view the pages. Several methods are employed to reduce the size of a Web site, and so decrease the download and layout time. To begin with, it can replace GIF images with compressed JPEG images using a compression ratio defined by the user. It also adds image size and alternate description tags to a document, something that a good HTML author should do anyway. Finally, Bandwidth Buster can remove images altogether to create a text-only alternative Web site. This useful feature will allow those who use a text-only browser to view the site.

CSE 3310 HTML Validator

This program, for Windows, checks HTML documents to make sure that they comply with the HTML 3.2 syntax. When it examines a document, it produces a list of errors, if any, that exist in the code. The software also supports Netscape and Microsoft extensions, as well as tags for tables and frames. More useful, is the option to add your own HTML tags, so it can be updated to be compliant with HTML 4.0.

HTML syntax cannot be checked with a standard browser, because it is only designed to view HTML documents. If there are any errors in a document, a browser will display the page how it assumes to should look. This means that a page could look different on a variety of browsers and, in extreme cases, may not appear at all. By using Validator, an author can be secure in the knowledge that the document will appear the same on all browsers.

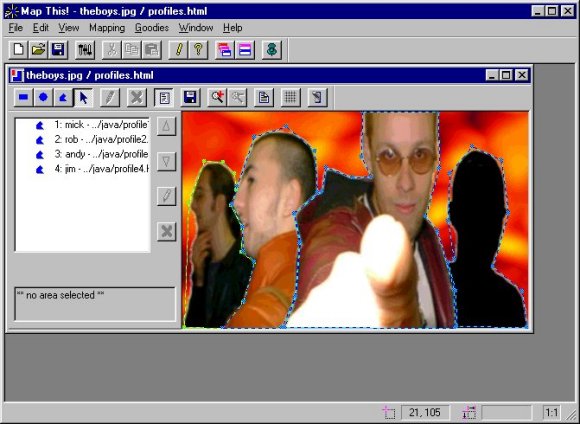

Map This!

Map This! is one of the more popular tools for creating images maps, and is available for all the major platforms. The program is free, and is used to create image maps within an HTML document without having to manually construct code. To use Map This!, an image must first be placed within an HTML page. The page is then loaded into Map This!, and the image for the map selected.

Once the image is loaded, selectable hot spots are then created on it. Map This! asks for the URL to be linked to these areas, and any alternative text for those who do not use graphic browsers. The code for the map is included in the page when the document is saved.

Figure 5.4: Map This! is a freeware program used to create image maps.

InContext WebAnalyser

InContext WebAnalyser, for Windows 95, is used to detect any broken links within a Web site. This helps to prevent anyone accessing your Web site from receiving an annoying error message when a link cannot be found. WebAnalyser quickly gathers all specified information about a site, and them displays the results graphically, like a directory structure. An icon with a circle and a slash represents a broken link. By selecting this icon, the user can launch an editor to correct the offending link.

Contents